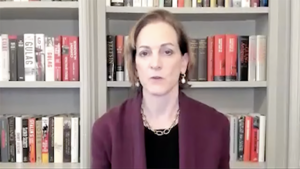

What is the role of social media in our politics today?

To discuss, we are joined by Renée DiResta, a leading analyst of the internet and its effects on politics and society.

As DiResta explains, social media platforms today are significant sources of political power that are fundamentally different from traditional media like newspapers, radio, and television. Social media makes users active participants in the consumption of information and algorithms have reinforced the polarization in our politics: “Algorithms key off of things that you like, things that people who are like you like. And then when that happens, you are put into these buckets, where you’re going to see more of a certain type of thing, so those identities are reinforced.” DiResta considers the ways in which Elon Musk has changed X (formerly Twitter), the power of controlling a social media platform, and the importance of this new phenomenon in politics at home and abroad. DiResta also shares her perspective on positive and negative effects of social media, from the highlighting of new perspectives to the proliferation of conspiracy theories.

DiRESTA: Now the man who is giving addresses from next to the Resolute desk is also the man moderating what voices are heard on social media…. Listen to how Elon describes USAID. I mean, it’s insane. Regardless of what you actually think about USAID, the man standing next to the resolute desk should be giving out accurate facts. And instead, any random anon who misreads a spreadsheet in a way that appeals to Elon’s sensibilities gets retweeted. It’s seen 30 million times. Because these people are so distrustful of institutions, the conspiratorial view of the universe holds. And unless they hear it from Elon as a correction, or maybe in the form of a community note as a correction, they don’t actually trust the correction. They don’t believe the media fact check. It never breaks through. Some of the people who are out there making the boldest statements... “USAID is behind the Trump impeachment,” is one of the stupidest stories out there. But Mike Shellenberger wrote it in his newsletter, and then Mike Benz said it on Joe Rogan. And this is audiences of millions of people, and they write very carefully, but they say the thing, and know their audiences trust them and are not going to believe the correction. And they’re not going to believe... They’re never going to walk it back. But that’s the sort of divide that we live in at this point. There’s no evidence offered beyond the theory, but that’s where we’ve kind of gotten to.

DiRESTA: When I say the word propaganda... so much of it is related to activation, just getting people who already believe a thing to act on it. And when you have the capacity to sort people algorithmically and to show them content that is tailored to them and get them to [act]… I want to make really clear here also that the public is not passive. People who are on social media have a lot of agency. I think everybody thinks like, “Well, I have agency when I’m on social media, but those other people over there don’t.” No, that’s not true. Everybody’s experience is just like yours. And so when we say, I always think about the phrase, “it went viral.” It just magically happened. No, people hit buttons, they did things. And I think we don’t think in terms of collective behavior, but that is what social media is for. It’s like assembling a murmuration of starlings or a school of fish, where, all of a sudden, everybody spontaneously assembles in a particular direction. The cues, the social cues that bounce from person to person, that’s what social media is for. And so [beginning around] 2012, some governments realize it, and ISIS realizes it, to draw that example, and then Russia realizes it. Russia invests very heavily in online propaganda to justify its invasion of Crimea. These are to support the little green men, you have the social media flood the zone. Saudis do it. This is how they sort of flood the zone, make it too hard to know what’s true. And that’s where you start to see the realization that these are tools of power.

DiRESTA: Elon Musk, when he bought Twitter, significantly changed how content was weighted in the feed. “Blue checks” all of a sudden were for sale, and their content would be ranked higher, their replies would be ranked higher, and people could monetize. And what I was referencing earlier, influencers who wanted to make money wanted to be more sensational, and then the algorithm would curate that, would curate that content, because people would engage with it. And so you would see a very different style. Like your feed, when people say, “My feed on X is totally different now,” that’s because the incentives are different and the way that it’s ranked is different. And the person who controls that is X, which is now owned by one person. So what’s the alternative? It’s to move to platforms where you have better control over your own feed. Unfortunately, right now, Bluesky is really the only thing that’s doing that. It’s new. I think it’s still kind of read as like, “lib Twitter” because of the sort of early adopters. My hope is that that opens up and more people come because of that granular control, because you really can control your feeds. I think Threads is starting to get at, again, this, “here are different ways that you can view your feed.” Maybe other platforms will start to move into that mode.

DiRESTA: I had an anti-vaccine account [on Facebook] so I could follow anti-vaccine news without it polluting my main feed. And that account would get recommended flat earth content. It would get recommended chemtrails content. And then I would join the flat earth and the chemtrails groups. And this account never posted, it just joined. And then after the chemtrails, I started getting Pizzagate, right? This was around the election, around 2015, 2016 timeframe, so the Hillary Clinton emails and all that stuff. And so I wind up with Pizzagate. And then I logged back in for something. I wanted to get some screenshots related to some of the chemtrail stuff that I was paying attention to. And I wound up seeing QAnon content. And this was before QAnon was really in the news. This is a hill I’ll absolutely die on: QAnon wouldn’t have existed to the extent that it does today without the recommendation engines pushing all of those people into that group, into those groups. There were many of them by that point. There were hundreds of thousands of people in these groups because the algorithms were bringing them together. Because as far as they were concerned, the highest good, if you will, was an active group, because an active group for them, because what they were optimizing for— “show me the incentive, I’ll show you the outcome.” The incentive, the optimization, is: getting people talking. Well, conspiracy theorists will talk all day long, because they’re in there digesting the “Q drop.” And so they’re in there trying to figure out where the pedophiles are, where the children are, or whatever. And these are incredibly active groups.

DiRESTA: One of the things that you really see on the internet is people assembling into very identity-based groups. And this happens partially because of culture, partially because of particularly polarized culture, the internet is reinforcing that. Algorithms though do key off of things that you like, things that people who are like you like. And then when that happens, you are put into these buckets, if you will, where you’re going to see more of a certain type of thing, so those identities are reinforced. And what you start to see is people will also really become very passionate defenders of some of those political identities in particular. They’ll put an emoji in their bio so you know exactly what they are the minute that you see them, and then they’ll fight with other people who are on the other side, in a different tribe. So that dynamic is very real. But I kind of got into studying this in part as an activist, not as an academic, because I wanted to pass a pro-vaccine bill in California as a pro-vaccine mom. And I think every time people start looking at something, they think like, “Oh, this just happened, this is the very first time this happened, this is completely new.” But I started reading about anti-vaccine narratives and realized that you could actually go back and pull up the British Medical Journal archives from the 1800s, and it is the same stuff. “The vaccine is going to kill you, it’s anti-God, it comes from cows and it’s going to turn you into a human-cow hybrid….” Right? They’re talking about smallpox— And the algorithm changes the targeting. So, content and distribution are two separate things. Content is what you’re going to read, what you’re going to pay attention to. Sorry, let me actually differentiate that. Content is what you’re going to read. It’s the substance of the stories. It’s the narratives themselves. But what you’re going to see is a little bit more targeted for you. So there’s a whole bunch of different stories out there in the world that could describe a particular phenomenon and they can all be inflected for your particular identity. And so as a pro-vaccine mom in California, I can read... I was reading a story in the New York Post this morning about... It was sort of going viral on X. There’s a relative of JD Vance’s who is trying to get a heart transplant and her parents don’t want to have her vaccinated, so she’s not eligible. So this is going to outrage everybody for entirely different reasons. And so it’s going to be targeted to people using very different framings, even though the facts of the story are the same.